|

Many of our on-the-fireline meals were K-rations. This

was canned food in OD (Olive Drab) colored tin cans and each ration kit (in a very thin, small cardboard box), came

with a small can opener called a P-38. There were canned meat, beans, fruit and bread. These were not as good as today's

military MREs (Meals Ready to Eat).

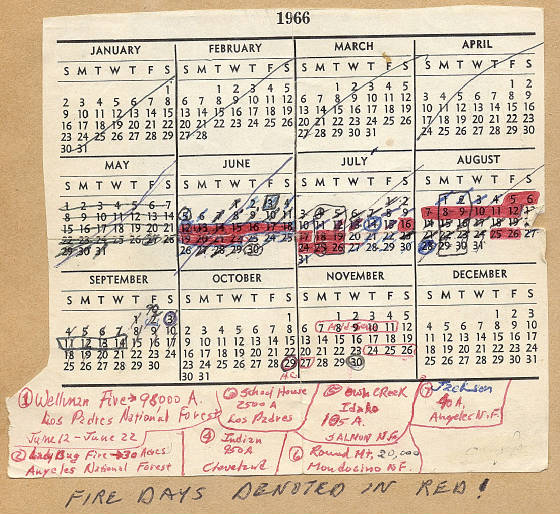

I kept a calendar and highlighted in red ink, the days that we were on fires. I listed the fire

names and acres burned below the calendar months. Our first fire was the Wellman

Fire, on June 12 and it was approximately 92,000 acres. I had listed it at 98,000 acres on the calendar, but the total acres

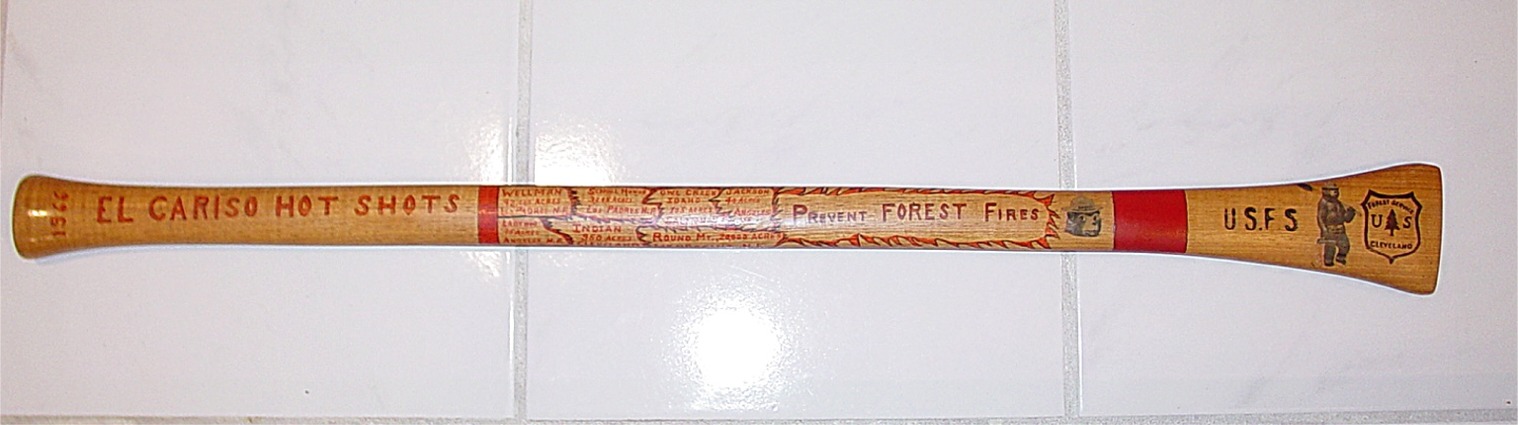

were later revised to 92,000 acres and that is what I have printed on the Fire Stick I

made. I was on 7 fires that summer.

|

1966 Calendar - Fire Days in Red |

When

fire tools became worn or damaged and unsafe to use, the wooden handles were cut off. We were allowed to

a make a souvenir “Fire Stick", listing the

fires we had attended. This was an El Cariso Hot Shot Crew tradition.

Below is the Fire

Stick I made from a Pulaski handle. I believe it was from an

actual Pulaski I used during that summer of 1966. It would be great if El Cariso had a collection of these

Fire Sticks from former El Cariso Hot Shots on display at their facility.

|

My Fire Stick |

I was assigned a Pulaski for most of the summer and occasionally a Fire Shovel.

I was the “first Pulaski” near the front of the tool line up. There were usually three Brush Hooks at the head

of the tool line up. I was part of a Hot Spotting Team, which consisted of a Pulaski, Fire Shovel and a McLeod.

Should a small spot fire break out, the Hot Spotting Team would leave the crew and work the hot spot as the remainder

of the crew continued to build fire line. When I was on shovel, I was the last man on the crew, touching up the line and making

sure that all flammable material was removed as the fire line construction was completed. Sometimes I would use a McLeod and

rarely a brush hook. I hated using the brush hook as I never really got the hang of it. It tended to bounce off the brush

when I tried to cut with it! The

Pulaski (combination axe and grubbing hoe) was my favorite. The Fire Shovel had a sharp cutting edge and could be used for

digging, scrapping and light cutting. The McLeod was a combination rake, scrapper and cutting tool with a sharp edge on the scraping portion.

The brush hook was used primarily for cutting brush but it could be flipped and the dull edge side of the blade used

for light scraping in an emergency. There was an “official tool line up” or that is, a designated order of specific fire tools assigned

to each man on the 15-man crew. I forget the actual number of tools in the various positions in the tool

line up of each 15-man crew. Brush hooks were at the head, followed by a Pulaski or two, a McLeod, a shovel, and then several

McLeods and maybe another Pulaski and brush hook with a fire shovel at the end of the line to finalize the construction. Team work was a necessity in fire line construction.

Ideally each man on the crew did his share of the work, pulling his own weight. The crew would move forward

cutting and throwing brush at a steady pace, as if it were some kind of giant cutting machine! It was amazing to me at times

to see how rapidly the fire line was completed. But of course, this depended on the brush type, terrain, etc. I do not recall

who scouted the location of the fire line, but I believe it was the foreman of each crew, and occasionally, the lead brush

hook. I recall only one time a chainsaw

operator was brought in to help cut a fire line. The brush was very tall and dense and it was slow going with hand tools.

A special chain saw operator was used to run the chainsaw and he was not part of the El Cariso organization.

Most chainsaws in those days were bulky and tiring to use for very long. I recently learned that

Hot Shot Crews these days routinely use chainsaws in fire line construction. One tool we loved to see on a fire was the “Giant Yellow McLeod” AKA: D-8 dozer

with a ripper on the back. Unfortunately, bulldozers had limited use on many fires due to the extreme steepness of the terrain,

but where they could be used, we were thankful. The ripper helped in going down hill as it was dug into

the ground to serve as a sort of anchor to help prevent sliding of the dozer. I recall one time we had

to lift a cotton fire hose over a D-8 to keep it from running over the hose line. With one guy standing on the track on one

side, and another guy (me) standing on the track on the opposite side, the dozer driver moved the dozer slowly forward as

we walked the track in unison toward the back, dropping the hose on the ground. Mission accomplished. The goal of fire line construction was to remove all flammable material to mineral

soil and remove any roots which could allow a fire to burn under and across the fire line and to remove all over-head material

that could fall across the fire line. On average, we tried to maintain a 10 to 12 foot wide clear fire line and sometimes

15 feet. Width would vary depending on fuel, steepness of terrain, weather (wind), and if constructing a hot line, cold line

(through the green), or cold trailing (fire line next to a fire that had burned out). Tool safety and maintenance were important, just as wearing protective equipment and

clothes like leather gloves, hard hat, high top leather boots, long sleeve fire shirts, and heavy cotton trousers (green jeans).

Maintaining a safe distance between Hot Shot crew members during line construction was also very important. And,

moving forward in the building of the fire line, and not backing up, was also. One time a guy just ahead of me with a Pulaski,

kept working backward and was too close. I was bent over digging roots with a Pulaski. He swung his Pulaski at a bush stem

and either missed or it ricocheted and swung around and hit my hardhat on the left side, nearly knocking me down. I was lucky!

There were occasional

injuries and blisters on feet and hands were common. I think it was Mark Turnham that fell on a Yucca plant and the hard sharp

pointed leaf went through his forearm. Someone contracted a bad rash from exposure to poison oak or ivy. All kinds of hazards were encountered. I recall one night, either another crew

or dozer was working above us and rocks were coming down the mountain. You could hear them rolling, then silence, which meant

the rocks were airborne, then a snap or cracking sound when they were back on the ground again. This would repeat for several

seconds. They were very hard to see at night with just headlamps on the hardhats. I recall lying still and flat on the ground

facing uphill, to be as small of a target as possible. You could hear some “swish” sounds as rocks flew by! Finally,

we were able to move from that area out of that particular danger. When fire tools were handed off to another person, the person holding the tool would

ask: “got it?” and the person receiving the tool would answer: “got it!”,

when they had the tool safely in hand. Jim Brown recently reminded me of this procedure. Fire tools were sharp and could cause

some pretty nasty cuts. When tools were left on the ground for some reason, they should be left in such a manner as not to

be a safety hazard, like place the shovel with the cutting edge face down in the soil. Also proper hand carrying of fire tools

included keeping them with a safety guard on until ready for use and carrying them by your side with the sharp edges or points

faced down. There was a permanent Helibase

and the El Cariso Engine Station directly across the highway (Ortega Highway) from the El Cariso Hot Shot Camp entrance. A

tanker truck crew and a helitack crew were stationed there. I have no memory of their facilities. I do not recall much about

their operations as I just don’t remember having much contact with them. I do not know who served as a pilot for the

helicopter. They had a tanker truck for hauling water to spray on fires similar to a fire truck, but more maneuverable on

the narrow dirt or gravel mountain roads. In the Southeast United States, in the US Forest Service, such a truck is referred

to as a “pumper”. Forest Service tanker trucks carried either a one and a half inch or two

inch diameter cotton hose in sections that had to be connected with brass connectors. I don’t recall

the diameter. I think the old fire hoses were cotton hoses, canvass like material, however, now they use a synthetic fiber

like polyester or nylon filament. I forget how long each hose section was. Some are 50 feet. There was

a large brass nozzle which allowed for adjusting the spray. The hoses were quite heavy when charged with water.

It took time to connect and lay the hoses as well as considerable time in retrieving them. This was Okay if you didn’t

have to move the truck a lot. There was also a one-inch diameter rubber hose on a large reel that could be pulled out fairly

rapidly and rewound more quickly than the large hose lay. The old reels had to be hand wound but newer ones had electric motors

for the rewind. The

helitack crew consisted of two men, the best I can remember, that suited up in heavy protective clothing and face mask and

helmet. They would jump from a hovering helicopter from about ten feet off the ground into dense brush

and clear a landing area called a heliport for helicopters to shuttle men, equipment and supplies to a remote fire location.

The El Cariso Hot Shots that summer consisted

of two 15-man crews. Crew 1 was assigned to the Ford crew truck and Crew 2 to the Dodge truck. I do not know the year or model

of these trucks. There was a foreman for each crew. John Moore was foreman of Crew 1, the crew I worked on. Ron Olson was

foreman of Crew 2, the crew Tom Graham worked on.

According to Doug Campbell, in the early years of the El Cariso Hot Shots and when the camp was being constructed, they

wanted some kind of Mascot. Doug’s wife Pat came up with a drawing of the “ruptured duck”, shown as beat

up by fires, various injuries and being struck by a lightning bolt. This was the Logo on our two crew trucks during the summer

of 1966. More information about the creation of the "ruptured duck" logo is discussed under "Doug Campbell"

as listed in the menu.

Doug also stated that Gordon

King, El Cariso Hot Shot superintendent that summer, derived the idea of the El Cariso Hot Shots wearing a Green Beret, similar

to the US Army Special Forces. This would be a symbol of the El Cariso Hot Shots, instilling a sense of

pride and team spirit in the organization. I was not able to confirm when this tradition began.

I have been informed that to earn the privilege of wearing the El Cariso Green Beret, that is, to qualify, one had

to have performed the construction of a fire line next to an active fire, that is, hot fire line construction. The insignia

for the Green Beret consisted of a curved piece of red plastic with El Cariso Hot Shots in white letters and a pin indicating

the year. The new guys who came to work without fire experience were referred to as “green kids” until they had

been on several fires. One had to have performed fire line construction on several "hot" firelines to be considered

eligible for an El Cariso Green beret.

During the summer, some personnel would leave and new members would join the crews. Usually the fall of the

year, brought changes in personnel, due to people going back to school or college or other jobs. Also in 1966, the Selective

Service was running overtime sending out draft notices and I understand that several El Cariso Hot Shots were drafted into

the military not long after the end of summer in 1966. Tom

Graham and I left the El Cariso Hot Shots to return to college. I returned to Texas on September 2, 1966.

The following crew

photographs were made in October 1966 according to the date on the back. I do not know who made these two group photographs.

The photographs of the two crews were sent to me by Rodney Seewald.

Left to Right, Back: Joel Hill, Steve White, Jay Shilcutt, Steve Bowman, John Verdugo,

Bob Chounard Middle:

Dan Moore, Rodney Seewald, Bill Waller, Andy Silkwood, Jim Reichard, Jim Mooreland Front: Ed Cosgrove, Jim Brown, John Moore

From Crew 1: Joel Hill, Steve White, John Verdugo, Dan Moore,

Bill Waller and Jim Mooreland all died from burns they received on the Loop Fire

of November 1, 1966.

Left to right, Back: Glen Spady, Pat Chase,

Pete Achberger, Fred Danner, John Figlo, Joe Smalls, Mike White Middle: Jerry Smith, Joe Beaty, Ken Barnhill, Frank

Keesling, Tom Rother Front: Richard Leak, Raymond Chee

From Crew 2: John Figlo, Mike White,

Ken Barnhill, and Raymond Chee, died from burns received on the Loop Fire of November 1, 1966. Carl Shilcutt and Fred Danner died in the hospital at a later time.

|